For people working in the field of accessibility, we are very much aware that accessibility benefits everyone, not just people with disabilities. Like Billy Gregory’s widely-shared tweet from 2015 said, “When UX doesn’t consider ALL users, shouldn’t it be known as “SOME User Experience” or… SUX?” In my case, I’m a non-native English speaker who works in accessibility, and I’d like to share a few things from the field that have helped me integrate into a new country with a language that isn’t my mother tongue.

Whether I’m watching Netflix or assisting at a meetup or a conference, I activate the closed captions. Why, you ask?

It helps me to not miss important information when I’m unfamiliar with the speaker’s accent, when the dialogue is too fast for me to easily follow, or when there’s background noise. On top of that, a speaker who uses idioms or slang can be even more difficult to follow. (And if the captions are automatically generated, they rarely solve these problems because auto-captions aren’t accurate most of the time.)

When I’m watching recordings of conferences or meetups, if there are transcripts available, that’s even better because that lets me go back to see whether I’ve missed any parts without having to stop a video. As with auto-captions, auto-generated transcripts aren’t very accurate either (some interesting examples can be found in Adrian Roselli’s article “Don’t Rely on YouTube Transcripts”).

Using closed captions and transcripts together can help improve one’s listening comprehension and speaking skills. Following along with a transcript and listening to how a native speaker pronounces words can improve one’s pronunciation and expand one’s vocabulary. This can also help native speakers improve their pronunciation of words that are often mispronounced.

This brings me to another important aspect of accessibility: the use of plain language. I’ve yet to hear someone complain that some text was too easy to understand. The simpler the text, the easier it is to understand, right?

Plain language makes text or conversation more inclusive to those whose mother tongue may not be the same as the text they read (or listen to).

As mentioned previously, using idioms or slang can create a barrier for some audiences because their localized meanings often get lost in translation. Even common idioms or slang used across English-speaking countries—such as the UK, the United States, and Canada—can vary widely.

Take these Spanish phrases which, when translated literally, can be quite confusing:

| Spanish | Literal English translation | Equivalent English phrase |

|---|---|---|

| Tener enchufe | To have a plug | To be well connected |

| En casa del herrero, cuchillo de palo | In the house of a blacksmith, knife of stick | The cobbler’s children have no shoes |

| Estirar la pata | To stretch the leg | To push up daisies |

It’s not just local idioms that can confuse—sometimes it’s a case of different words being used in different countries.

| Object | What an American person would call it | What a British person would call it |

|---|---|---|

| A mobile living area that’s attached to a car or truck | Trailer | Caravan |

| Toilet | Restroom | Loo |

| The third season of the year when it starts to get cold | Fall | Autumn |

| The part of the street next to the road where people walk | Sidewalk | Pavement |

That said, with some words, I don’t recommend trying to come up with a non-region-specific alternative because that may end up being far too verbose in the face of just accepting that that word isn’t used everywhere (such as sidewalk).

Lastly—but not least important—we need to be careful with the use of aria-label. If you haven’t made your webpage available in other languages, some users may rely on Google translate or other similar online translation services. While on-the-fly translations are improving all the time, some browsers don’t translate content that’s inside aria-label attributes, which means that screen readers will announce the content that’s in aria-label attributes in their untranslated form.

For instance, a search button:

<button aria-label="search">...<button>

If the aria-label isn’t translated, a Spanish screen reader user would not hear this as “buscar” as hoped/expected.

You can find some great examples in Adrian Roselli’s article “aria-label Does Not Translate”.

Assistive Technology to the Rescue

How you can improve your comprehension of sites that you’re visiting

To help me understand what’s presented, I use a number of options in assistive technologies in my day-to-day work as an accessibility engineer.

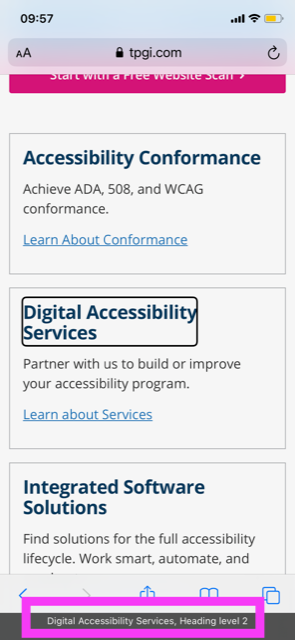

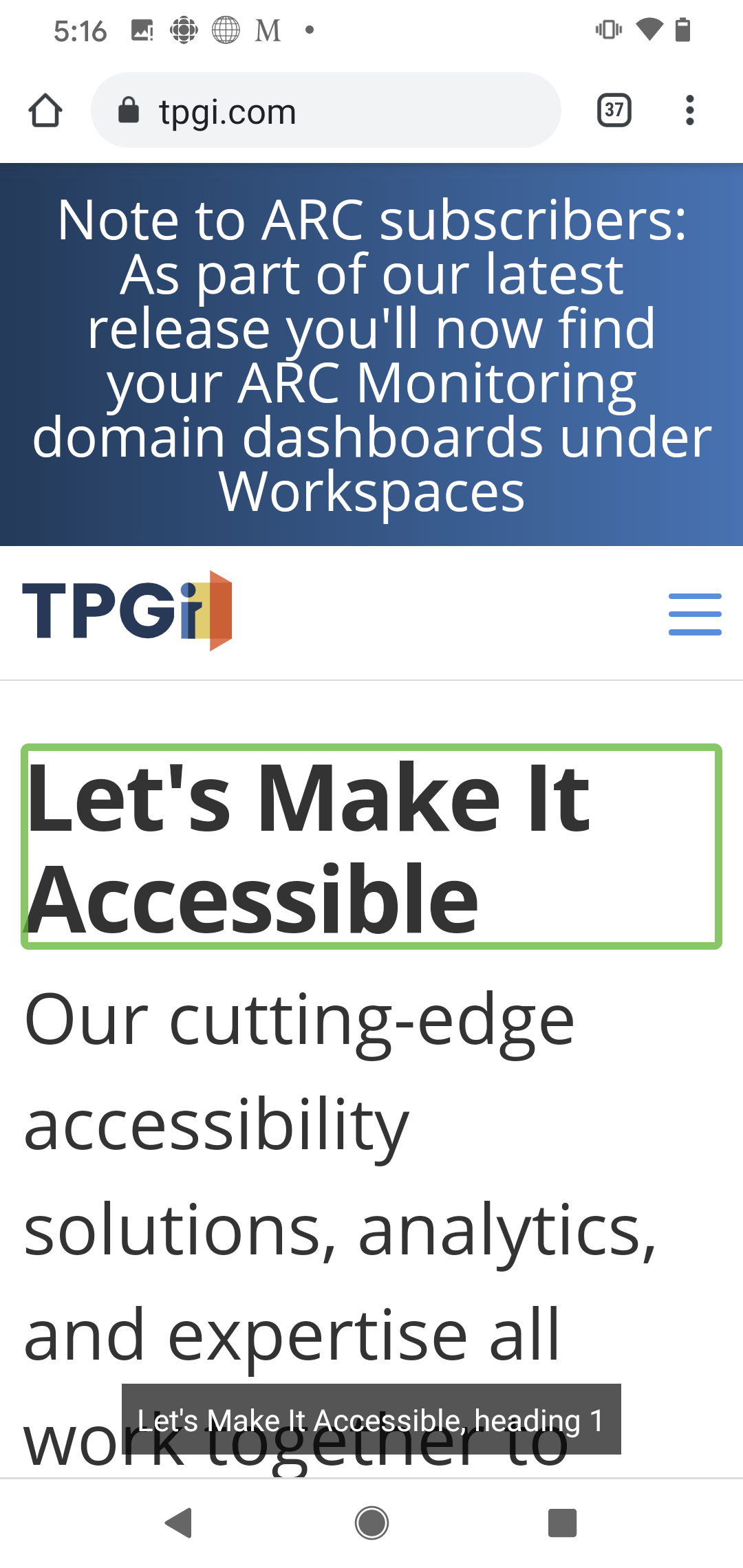

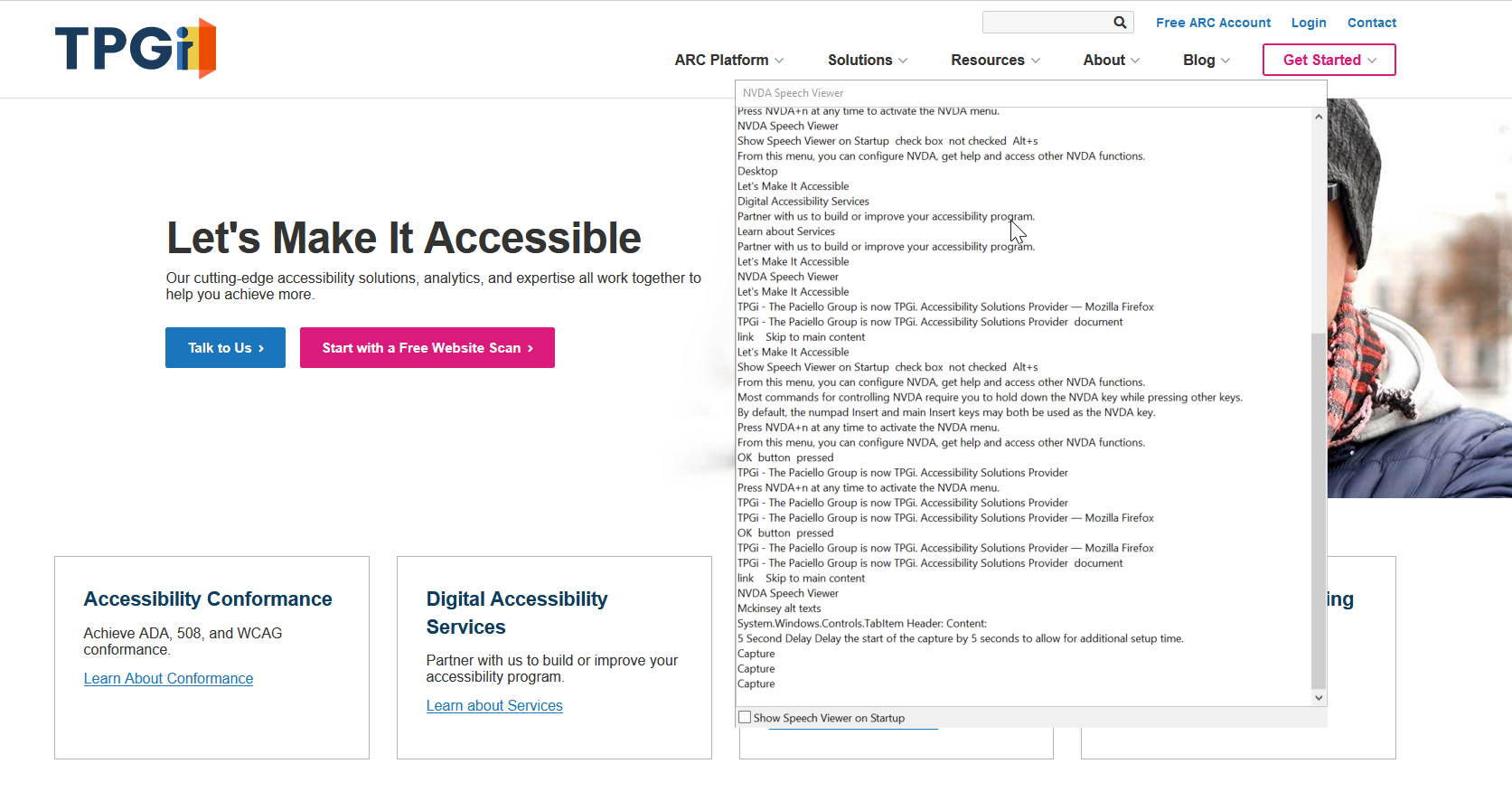

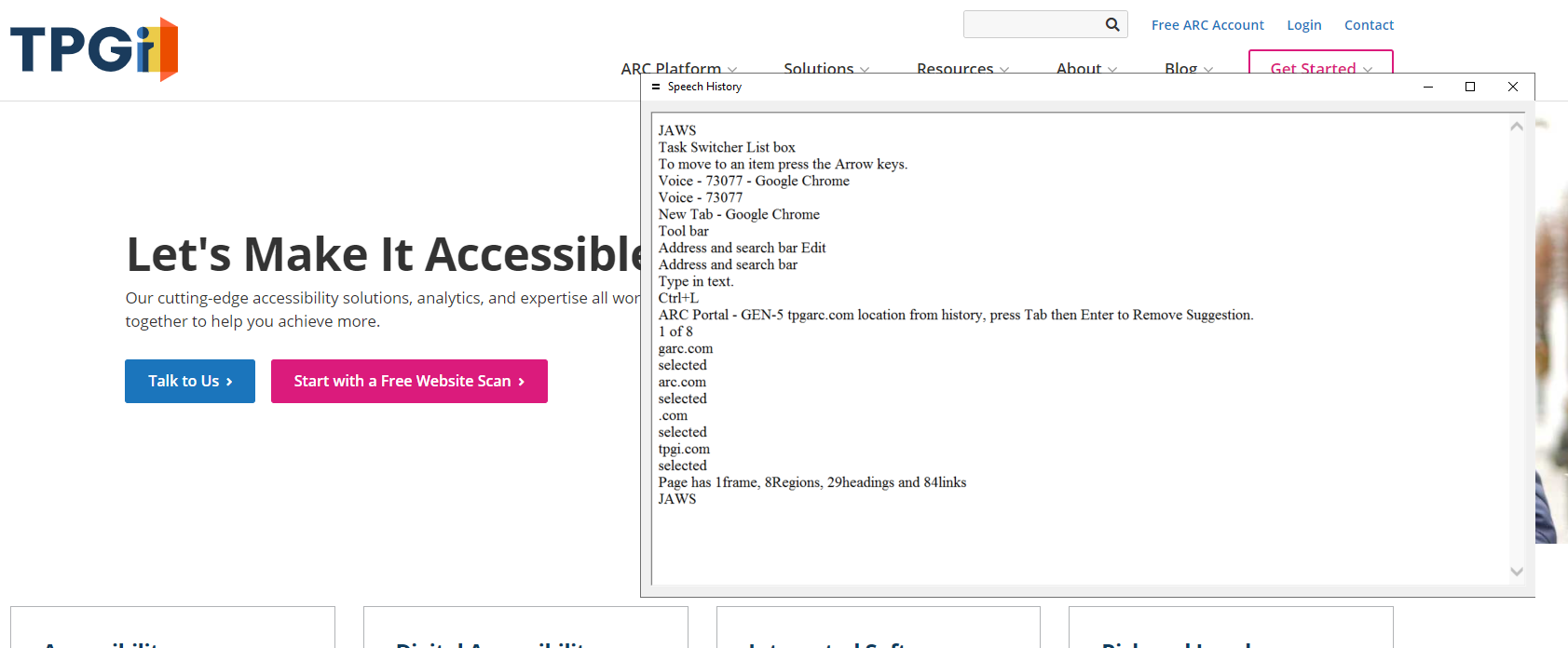

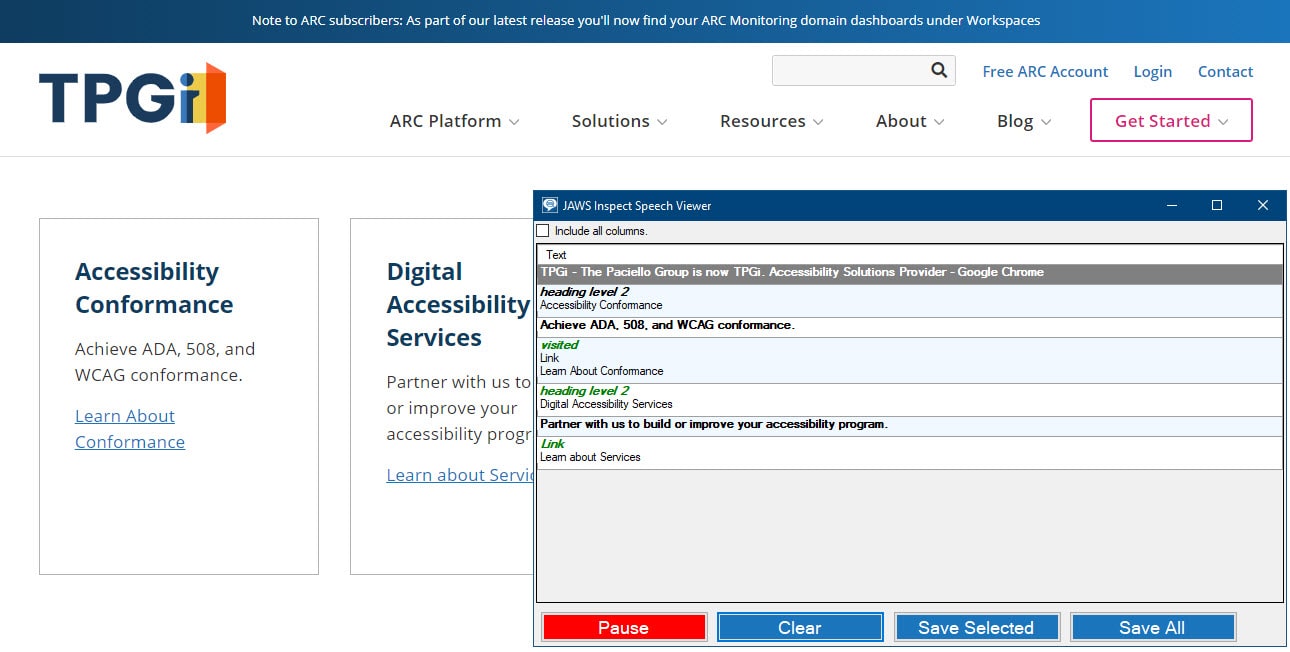

Being able to read text while it’s being spoken—whether that speech is coming from a human or it’s being synthesized by a screen reader—helps prevent me from missing important information. So just as I prefer to have closed captions on while I watch Netflix, I take the same dual-sensory-input approach with my audits. Screen readers—for desktop and mobile devices—typically have an option to display the speech output in a text format. Here’s how you can enable this:

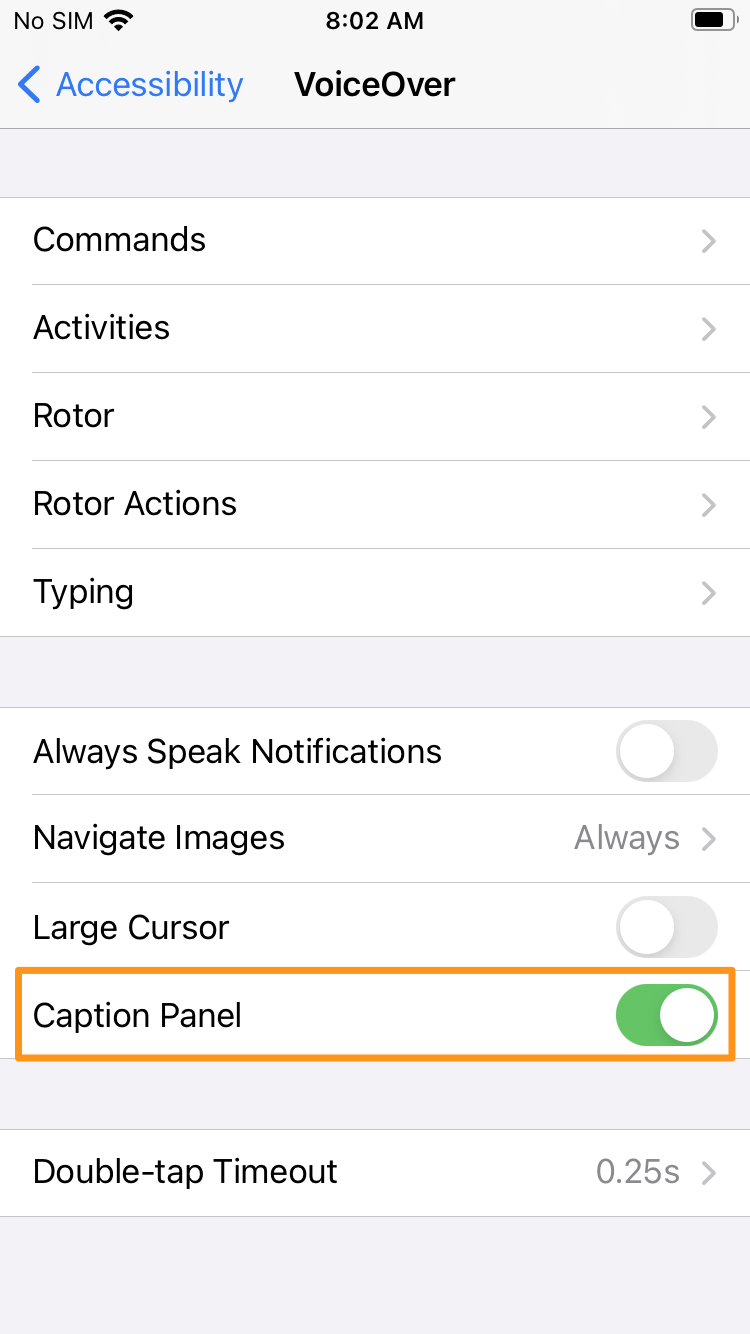

VoiceOver on iOS

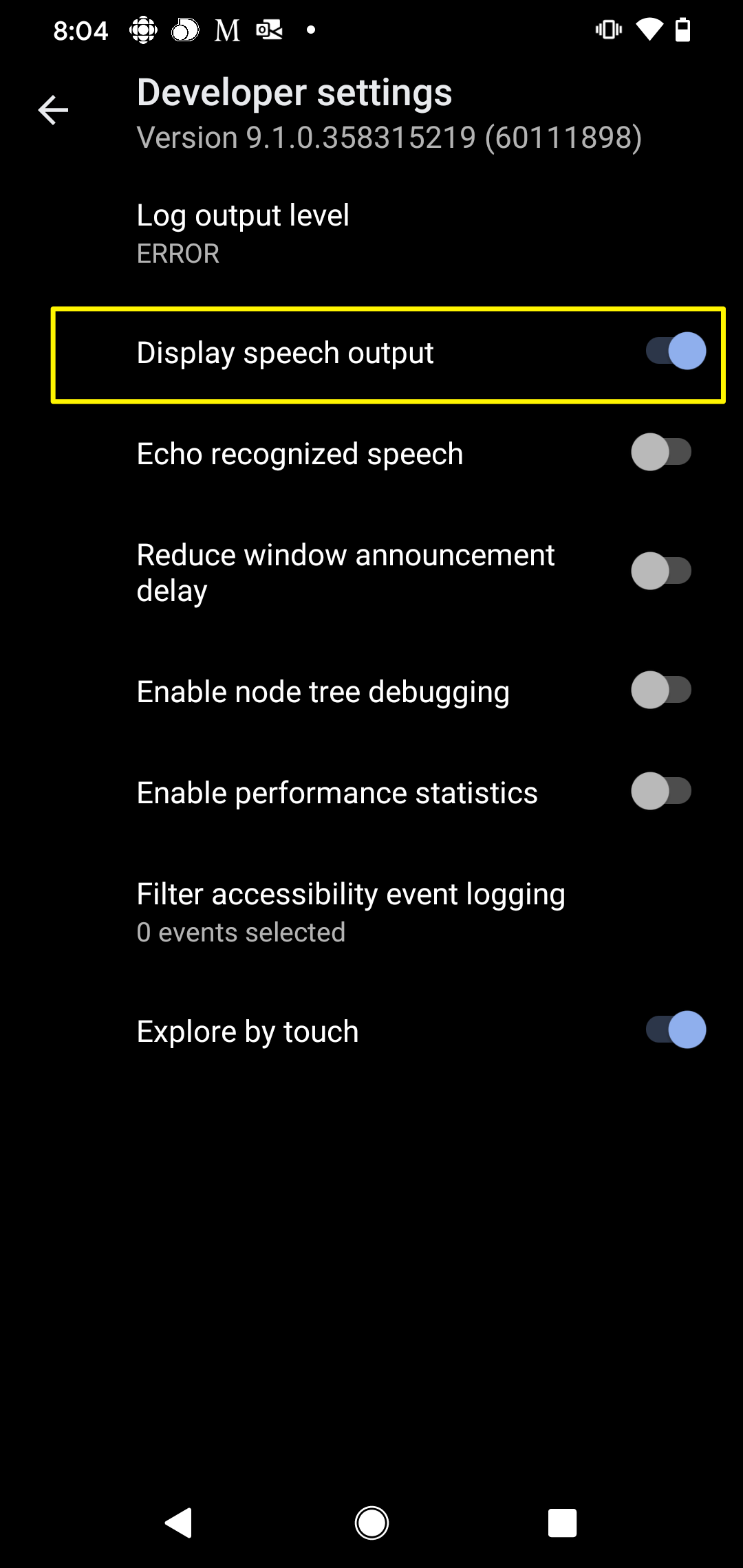

TalkBack in Android

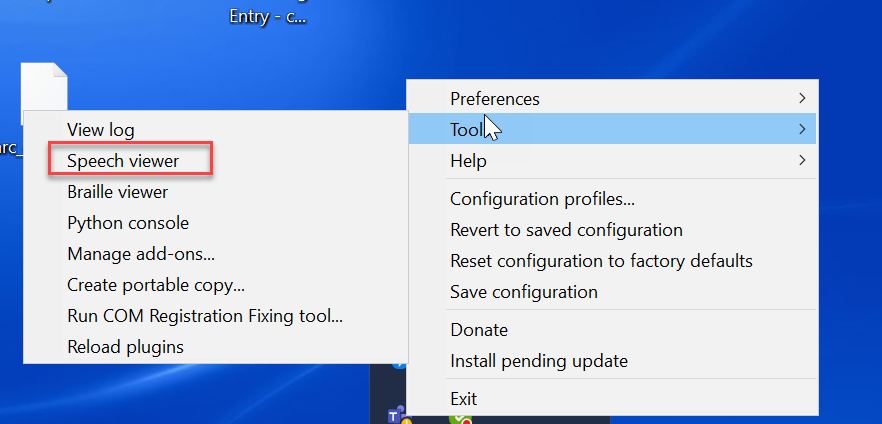

NVDA

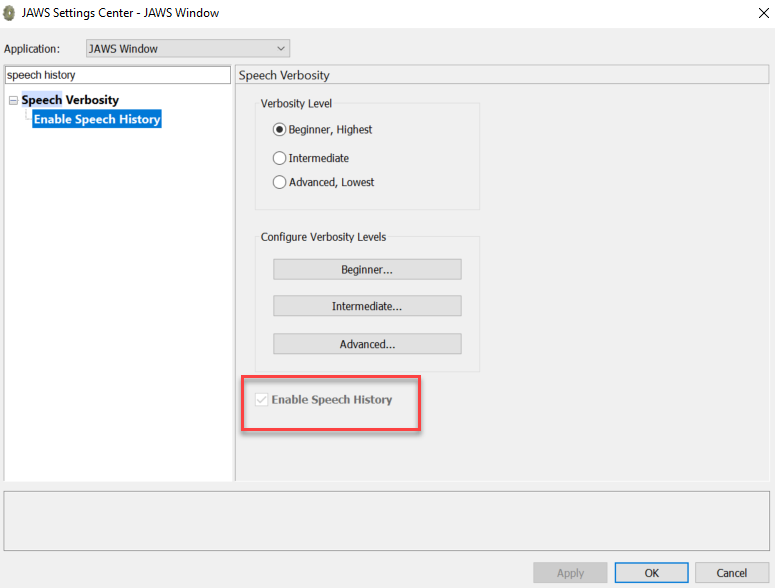

JAWS

The above tools and techniques can help create an inclusive world—not just for newcomers and people who are learning a new language, but for all users. Learning a new language isn’t easy, so let’s continue working to provide accessible content and improve existing tools to make it easier for everyone.

Related WCAG Success criteria

Check out some of the related WCAG success criteria below to find out how you can provide more accessible content:

Comments

Yes, as you say, Plain Language isn’t even always plain! Regarding “The part of the street next to the road where people walk”, in Melbourne Australia we call that a ‘footpath’.